Navigating the Fog: Software Investors’ Playbooks for the Next Cycle

Last decade’s SaaS winners made investors very rich. But as tailwinds recede and competition in software only increases, how will software investors make money in the next cycle?

As sentiment ticks up in Silicon Valley, software investors must grapple with a foggy long-term outlook

The Nasdaq is up more than 30% this year.1 Many pre-product startups in the YC S23 batch raised money at valuations north of $20M. Macro observers no longer treat a recession in the coming quarters as a certainty.

As summer turns to fall, many software investors feel something they haven’t felt in nearly two years: optimism. While nobody is naive enough to expect another bubble anytime soon, despair has faded, and hope (even if slight) has returned to Silicon Valley.

Given the brutality of the last two years, we shouldn’t fault investors for their excitement. But before we unlearn the lessons from the last cycle, we should take stock of what happened in software over the last fifteen years. Despite the enormous wealth generated by investors in the decade-plus following the Global Financial Crisis, many software companies haven’t lived up to the promise of their business model. That broken promise now has implications for private investors moving forward, with the outlook for software companies foggier than ever and old playbooks unlikely to work as well as they once did. Now, it’ll be harder for companies to win – and for investors who don’t refocus on new opportunities to make money.

After riding the first wave of on-prem software companies, investors had good reason to be excited about SaaS following the GFC

Let’s start at the beginning: the early innings of the SaaS boom. Investors had previously backed a generation of breakout on-prem software companies – Software 1.0 – which had built very strong business models. They were capital-light, sold to sticky customers, had low marginal costs of distribution, demonstrated significant operating leverage on high levels of fixed R&D costs, and benefitted from extraordinary cash conversion dynamics by collecting up-front payments for perpetual licenses.

By the late 2000s, investors were eager to capitalize on B2B software’s shift to the cloud. They piled into Software 2.0 companies – SaaS ones – due to the fundamental promise of the SaaS business model:

“Renting” software for long periods of time to sticky customers made SaaS revenue streams recurring and highly predictable and increased customer lifetime values

Delivering software via the cloud shortened sales and implementation cycles and made them cheaper

Cloud delivery enabled easy and continuous product updates, improving the customer experience and generating upsell opportunities

Investors banked on SaaS companies becoming highly predictable, capital-light businesses with high profit margins and ROIC. And secular tailwinds for software companies in the 2000s made the promise of the business model even more enticing:

Companies attacked attractive markets that were massive, underserved by technology, and growing rapidly due to continued digital penetration

The post-GFC economic recovery (and the bull market in tech) meant that customers – both large corporations and venture-backed startups – were growing and flush with cash for new tools

The advent of cheap and flexible cloud computing resources made software R&D much easier, creating a virtuous flywheel: the number of software companies exploded, which lowered the barrier to entry to building software, which led to the birth of even more software companies

Startups rode these tailwinds and created a straightforward playbook for company-building:

Identify white-collar workflows primarily orchestrated on pen-and-paper or with unintuitive on-prem software built by a sluggish incumbent

Digitize those workflows with a focused, elegant, cloud-based solution

Build additional features, permissions, analytics, reporting, and integrations with other apps

Of course, low interest rates post-GFC were the icing on the cake. Allocators hunting for yield increased their venture exposure, enabling the growth of the software ecosystem. With the opportunity cost of capital so low, private investors took an ultra-long-term view on future profitability and defensibility. Entrepreneurs had maximum flexibility to build their businesses and finance their long-term investments in R&D and customer acquisition.

Bona fide excitement eventually got out of control, turning into extreme bubble behavior for eighteen months following the onset of COVID

Over a decade of enthusiasm around software companies culminated in an extreme asset bubble. In the year following COVID’s onset, valuation multiples for the median software company peaked at nearly twenty times forward revenue, triple their long-term average. Wall Street’s darlings traded at even crazier valuations: the median multiple of the five most richly valued companies at one point reached eighty times forward revenue.

What were investors thinking? There are three charitable explanations:

The pandemic dramatically “pulled forward” growth. IT budgets expanded dramatically overnight to enable remote work for tens of millions of knowledge workers, making software companies extremely cheap on a short-term, growth-adjusted basis. The long software trade, in both the public and private markets, looked like a lucrative one

Many believed that the pandemic prompted fundamental changes that would lead to permanently higher growth rates: work-from-home would be widespread forever, even stodgy businesses would rapidly digitize, and headcount growth at any company adjacent to the tech industry would remain robust for years, justifying rosy long-term assumptions around selling seat-based licenses

Investors assumed that ZIRP would persist indefinitely, eliminating concerns about the long-duration nature of software businesses that might only start generating meaningful FCF far into the future

Investors told themselves some version of the story above. But the charitable view of their mindsets isn’t fully explanatory. Sophisticated investors, just like their retail counterparts who pumped meme stocks, were bored and nihilistic in the months following the pandemic, locked away at home watching the world seemingly collapse around them. When people felt like nothing mattered, deploying fat sums of OPM into exciting (and risky) businesses felt easy – and gratifying.

FOMO and greed obviously played a role too. Investors saw their peers getting unfathomably rich as the whole tech ecosystem went gangbusters. Pre-product startups and growth-stage companies alike, new IPOs, crypto, SPACs, and even bankrupt companies soared. People know that the most money is made in bubble times (if you’re lucky enough to sell to a greater fool before the crash). Even usually disciplined investors became reckless gamblers, indiscriminately deploying capital and hoping for the best.

We revere the big software wins: companies who redefined workflows, acquired thousands of customers, and created tons of wealth for their founders, employees, and investors. Lost in our discussion is the reality that many didn’t quite live up to the promise of their business model.

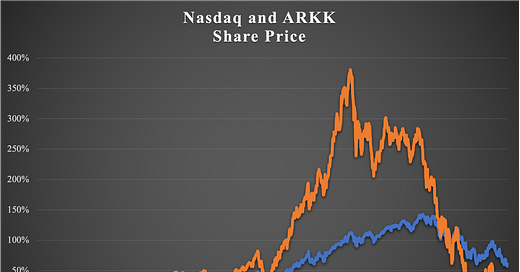

The bubble finally came to a head at the end of 2021. The Nasdaq peaked in November (although many of the ultra-speculative stocks, perhaps best represented by Cathy Wood’s ARK Innovation ETF, had actually peaked much earlier), and the months that followed saw extreme carnage for the entire tech industry: a 36% drawdown for the tech-heavy index by late 2022, plummeting token prices and several high-profile crypto blowups, similar stock movements for unprofitable SMID-cap software companies, a dramatic slowdown in the pace of venture and growth funding, and large RIFs at both private and public tech companies.2

Despite the collapse, the post-GFC bull market in software made investors very wealthy. The best investors took aggressive, non-consensus swings on companies building category-defining products. Others simply picked the right game, going long (and sometimes levered long) beta. It was sometimes hard to distinguish between the two. There’s nothing wrong with riding a wave – rather than generating real alpha – but those in the latter camp should tread carefully moving forward. They should take a hard look at their software thesis: has the bull case for SaaS companies as highly profitable played out?

Most public software companies still aren’t making money

Out of a universe of 81 publicly-traded software businesses, 56 (slightly more than two thirds) generated positive FCF over the last twelve months.3 That’s a fine number, but given that many of these companies were founded more than a decade ago, hardly a great one. And adjusting for stock-based compensation – a very real expense associated with hiring the talent required to successfully operate a business – the picture is much uglier: 65 companies (~80%) don’t make any money. I’m sure that number is close to 100% for the universe of private companies.

These winners ought to be reaping the rewards of their long-term investments, but the vast majority haven’t figured out a way to do so. Software permabulls argue that these companies could easily be profitable if they stopped “investing in their future.” That may be true for some, but not for most. Many of these companies don’t have underlying strong economics and choose to reinvest more than 100% of their profits to bolster their competitive position – they’re just burning down the large piles of investor cash they raised over the last decade.

Software companies may have an attractive business model, but they’re not special or off-limits from harsh scrutiny. Great ones learn how to make money. Marc Benioff, for instance, founded the now-iconic giant Salesforce in 1999. He took it public just five years later in 2004 and finished that year as a profitable business, doubled net income in 2005, and quadrupled it in 2006. The unfortunate reality is that many of the last cycle’s winners can’t do it. Indeed, their poor profitability results today are already much better than they were a few quarters ago following sweeping cost reduction initiatives that started last summer. “Companies were just responsive to investors who rewarded topline growth” is not an adequate excuse. They’ve explicitly tried to become profitable – instituting hiring freezes, re-negotiating vendor contracts, optimizing customer success costs, outsourcing low-level R&D labor to low-COL areas, killing speculative projects, trimming low-ROI marketing spend, re-focusing on their ICPs, and cutting extreme bloat throughout their organizations – and they’re still not making money.

It might be time to begrudgingly accept that the bull thesis for many software companies as fundamentally excellent businesses is simply busted. Can companies managed for years with an “abundance” mentality shift towards a permanent, sustainable orientation towards profitability? Buffett doesn’t think so:

Whenever I read about some company undertaking a cost-cutting program, I know it's not a company that really knows what costs are all about. Spurts don't work in this area. The really good manager does not wake up in the morning and say, “this is the day I'm going to cut costs,” any more than he wakes up and decides to practice breathing.

Profitability is a muscle, not a switch. Investing in growth is fine, but discipline around spend and establishing strong economics must be a core business principle from the outset. Too few founders and management teams have acted this way. Ultra-strong tailwinds and accommodative monetary policy helped them and their investors make money anyways, but with a much more challenging environment ahead, business fundamentals – and valuation multiples – may get worse. Generating strong returns will require more than luck and old playbooks: investors need to respond with new ones.

We’re not just riding out a temporary rough patch. Software companies today face a fundamentally different, more challenging environment than they did in years past

That many software companies never became the ideal version of what early investors hoped for, yet still made those investors enormous sums of money, should be a wake-up call to capital allocators facing a challenging environment ahead. Even as markets have ripped higher in recent months, many investors seem to understand that money-making won’t be as easy as going long a broad basket of software companies. Dan Loeb summed it up nicely in a tweet last year: “I don’t think camping out in the last decades’ darlings… will be the winning strategy.”

Market tailwinds have dissipated

Software companies no longer benefit from the tailwinds they rode over the last fifteen years. End markets are still quite large – larger than anyone imagined – and many are far from fully penetrated. But future growth will be much harder to come by:

Obvious buyers of software have already adopted digital tools. There will always be customers looking to digitize their pen-and-paper workflows and improve legacy systems with newer, higher-quality solutions. Companies are now on the harder part of their customer acquisition cost curve – customers will take longer to acquire, and it’ll be more expensive to acquire them

The raging bull market in the tech industry is over. Headcount expansion among customers won’t be so strong, depressing growth for companies with seat-based pricing models. And buyers have become much more cost-conscious as CFOs have taken the reins. Deals will be smaller, they’ll take longer to close, and expansion opportunities won’t come as easily

Markets have matured. Companies must fight many competitors, not only in their core markets, but also in the adjacent (or entirely new) ones they’d like to enter to kickstart their next phase of growth

What do maturing markets and crowded competitive landscapes mean for business fundamentals? Most companies should expect higher customer acquisition costs, slower new logo growth, and lower net revenue retention.

These headwinds are strong for incumbents and even stronger for startups. Most end markets already have strong incumbents who have established solid footing; attacking them will be challenging. And the number of new, untapped markets is much lower than it was fifteen years ago.

Even startups who find real greenfield face a challenging road ahead. Startups have historically won by starting small and narrow, expanding over time: focus yields quality, and quality begets growth. But buyers now are much more cost-sensitive, leading consolidation efforts and squeezing their vendors as much as possible. Moving forward, startups with the highest-quality point solutions will struggle against well-capitalized incumbents who build copycat features and/or acquire them via M&A to create lower cost-per-SKU, bundled offerings.

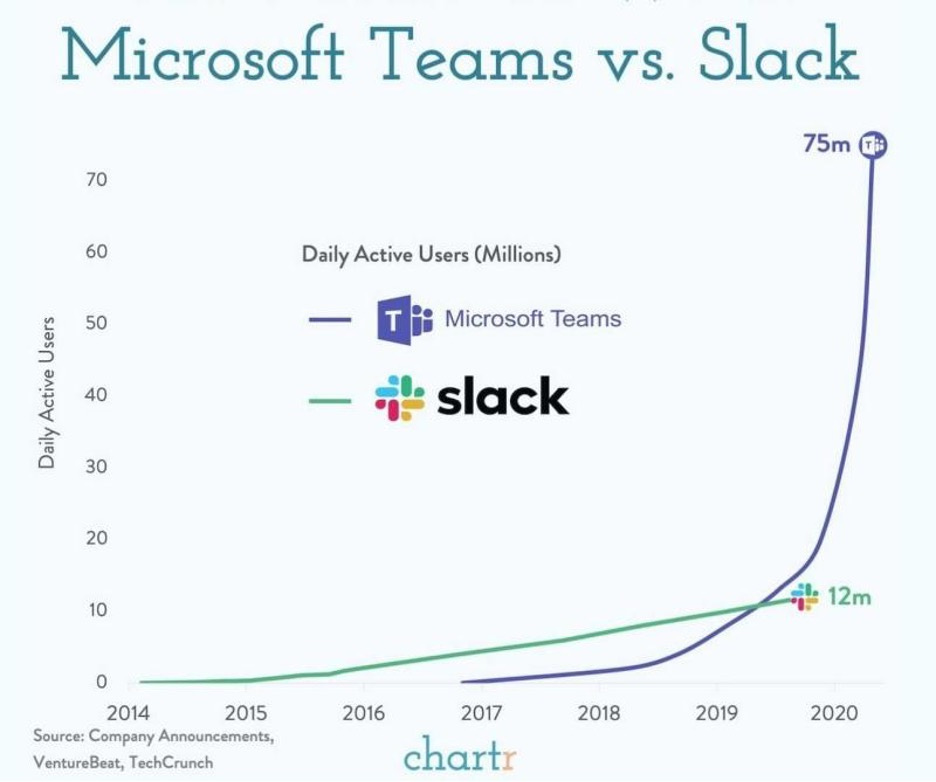

Although it wasn’t a “startup” when this happened, Slack offers a high-profile cautionary tale: a huge incumbent (Microsoft) launched its own copycat feature (Teams) and crushed Slack’s user numbers within three years. Ironically, the company was subsequently acquired by Salesforce, becoming the pillar of the CRM giant’s collaboration strategy – a perfect example of the incumbent’s “copycat or M&A” playbook at work.

Similar dynamics will play out for dozens of narrow products in the coming years. Surviving long enough and consistently growing quickly enough to turn point solutions into platform products will be much tougher than in years past.

Competitive pressures are extreme, particularly in horizontal software markets

Maturing markets have made the competitive landscape especially harsh for horizontal software businesses, threatening their long-term value. Massive end markets for all sorts of horizontal apps justified huge capital investments into several companies within each space, enabling them to develop features, acquire customers, and generate significant revenue.

Now, armed with this capital, companies are fighting a feature “race to the bottom,” copying their competitors and attacking the same feature ideas as they strive to turn their point solutions into platform products. All but the best-in-class companies will ultimately become capital-intensive, undifferentiated players with large, hidden “maintenance capex” requirements: they’ll necessarily engage in expensive feature proliferation, not because it’s a true investment in service of long-term defensibility and profitability, but because they’ll have no choice.

These pressures exist for many incumbents, who successfully rode their first S-curve and who are now looking at the same new spaces for their second act. And they exist doubly for startups, who face competition not only from other new companies, but also now from incumbents who have started expanding into their own core market.

Take the companies attacking “back office” software solutions, for example: Gusto, Rippling, Deel, Lattice, Ramp, Brex, Airbase, Mercury, and more. While they initially focused on their own niche, they’ve begun encroaching on each other and slugging it out. All seem to understand that building durable, profitable companies will require becoming unified platforms that handle most (or all) of payroll, recruiting, employee experience, IT provisioning, card issuance, spend management, AR/AP, banking and lending, and accounting. Consolidation is inevitable, and it’ll be led by the one or two winners with the strongest system-of-record potential… I’m looking at you, Rippling.

The challenge for incumbents and startups alike isn’t that they can’t build great products: wonderful, feature-rich solutions for their customers. It’s that a great product doesn’t make a great business. Some companies will do just fine, leveraging their dominant competitive positions (and commensurate pricing power) to grow topline for many years. But many companies that might have taken growth for granted in the past will start feeling the pressure of the competitive environment, running out of luck and eventually slashing prices to win deals. When that happens, the blessing of the software model’s operating leverage will quickly become a curse: plateauing (or worse, declining) revenue can make high fixed costs a burden.

Generative AI, as exciting as it is, is not a panacea for new application software startups

Discussions among tech investors in 2023 have been dominated by generative AI. Where in the stack will value accrue? Will incumbents or startups capture the value? Should we pile into NVDA and go on vacation?

It’s been less than a year since OpenAI released ChatGPT, ushering in the age of generative AI. It’s too early to tell what it means and how things will shake out at all layers of the stack. But I’m skeptical that LLMs will kick off the next bull market in early-stage application software. Incumbents have moved remarkably quickly to incorporate LLMs into their products, and they hold many advantages over startups with respect to capturing value from it:

Compute is expensive – even as the cost of compute declines – which raises the barrier to entry for new startups and benefits compute-rich incumbents

Incumbents already have deep, long-standing relationships with their customers that they can leverage to distribute new, AI-powered features and products. Distribution is just as important as product

In addition to owning the customer relationship, incumbents have already built rich, feature-complete products and own their customers’ workflows. Weaving intelligence into those workflows is a much easier task than building new products wholesale – and then fighting to sell them. Except in spaces where best utilizing generative AI will require remaking products and workflows from the ground up, incumbents hold a huge advantage

Many out-of-the-box, large foundation models are not equipped to perform domain-specific tasks. Incumbents have access to mass corpuses of proprietary data on which they can fine-tune large foundation models (or train smaller ones) for their domain-specific use cases. Startups lack this data, making it difficult for them to build delightful, properly functional workflows in many spaces

AI is the most exciting technological platform shift since mobile, and major platform shifts always spawn valuable new startups. Some hot businesses are already showing signs of potential: Jasper (copywriting), Runway and Captions (video creation), Arena (enterprise decision-making), and Tome (automated presentations). The jury is still out on all of these, of course. Incumbents in these spaces will respond, and because they’ve generally moved quickly to date, generative AI may ultimately be more of a sustaining innovation than a disruptive one – at least in many areas of application software. I wouldn’t bet on the AI shift birthing the same number of generational companies as the cloud computing and mobile waves did over the last two decades.

Generative AI also creates structural business model challenges for all but the best companies

Generative AI also presents a fundamental shift in the underlying business model of software – and not a favorable one. High fixed costs (especially high up-front ones) have historically characterized the software cost structure, and while model training fits the bill, ongoing model inference is very much a variable cost of revenue. In the AI-driven software world, the assumption of low marginal costs no longer holds.

Even if AI-driven co-pilots help software companies reduce headcount (and spend) in parts of their R&D and G&A organizations, ongoing inference costs outweigh those margin improvements. This is true whether companies pay those costs indirectly (by calling a foundation model company’s API) or directly (if they host their own models). Until or unless technological advancements drive the cost of compute to nearly zero, it’s very likely that introducing AI features and products will depress the margins for many companies selling software.

Of course, pricing will adapt: more usage-based pricing, and perhaps more seat-based models that require incremental spend to use AI features (we’re already seeing companies like Notion make customers pay extra for access to new, LLM-driven features). But these models may make revenue streams less predictable than pure seat-based ones. And how easily a company can adapt its pricing model to offset higher direct costs will ultimately depend on what type of business it is and how strong a competitive position it has. The very best companies – extremely sticky, system-of-record products that delightfully weave intelligence into their existing workflows – will successfully price their AI-driven products aggressively enough to not only increase gross profit dollars but also increase gross margins relative to today’s baseline.

Conversely, I expect that many companies aggressively incorporating AI will ultimately generate gross margins lower than the ones they do today. These companies will likely fit one of two models:

Pure-play LLM products. For these companies, model inference is a cost of all (not just some) revenue, so they’ll generate lower margins than companies whose primary direct cost is cloud hosting

“Traditional” software companies (incumbents or otherwise) that layer on LLM-driven features but lack strong competitive positions

Pure-play LLM products will derive all their revenue from features that require model inference, so they’ll generate lower margins than companies whose primary direct cost is cloud hosting. Their margin profiles may ultimately resemble those of infrastructure businesses like Twilio. And while the more “traditional” software businesses integrating generative AI may generate only a portion of their revenue from features that require inference work, because they lack strong moats and commensurately strong pricing power, they’ll struggle to price their AI-driven features at the same gross margin as their core offering. Really weak companies may price their AI features at or even below cost, generating no (or negative) incremental gross profit dollars and depressing gross margins. Better businesses may price their offerings at cost-plus, at least generating incremental gross profit but still sacrificing gross margin. Either way, expect margins to decline.

Whether the cost of delivering AI features is explicitly passed on to consumers as an optional add-on or baked into the overall price of a product, only the highest-quality companies will avoid margin compression. A software world dominated by AI is one in which most software companies are less predictable and have structurally lower margins, ultimately weighing on their value.

Dissipating tailwinds, crowded competitive landscapes, and structural business model changes present challenges for software companies and their investors. The interest rate environment will likely act as an additional headwind to returns

Low interest rates following the GFC (culminating in post-COVID ZIRP) supported robust valuations for both public and private companies, playing a significant role in the wealth generation that occurred. The reverse was also true: as the “inflation is transitory” argument gave way to legitimate concerns about sustained inflation in late 2021, the Fed signaled that rate hikes were on the way, and the bubble finally burst.

Nobody should bank on another easy-money environment to propel valuations back to record highs. Even if the Fed successfully navigates the economy to a “soft landing” in which inflation falls to its long-term target of 2% without a recession, interest rates may settle higher than the ~2.3% that 10-year treasuries averaged in the five years leading up to COVID. And there are structural reasons why price levels may remain elevated in the years ahead, forcing the Fed to revise its long-term target upward:

De-globalization and an effort to onshore manufacturing will raise producer input costs

Establishing natural resource security and independence will raise energy prices, an important inflation input

Corporate ESG goals will raise all sorts of costs of doing business

Populist labor policies – supported by both parties now – will lead to higher wages

High levels of government spending (primarily on the military and entitlements) will boost price levels

Some argue that our aging demographics may ultimately be deflationary, but structural inflationary forces in the US are strong. If inflation stays above the Fed’s target, interest rates will remain well above their pre-COVID average, perhaps much closer to the 4.3% they sit at today – especially as the Treasury constantly floods the market with bond supply in order to finance deficit spending.4

What does this mean for software companies and their valuations? Tighter monetary policy and worse fundamentals – slower new logo growth, lower net revenue retention, higher customer acquisition costs, longer payback periods, structurally lower margins, and big questions around durability – will ensure valuations remain grounded. The market seems to understand this: you can’t win by fighting the Fed. The median software company trades at just 6.0x NTM revenue, a nearly 25% haircut from the 7.8x median multiple for the five years prior to the pandemic.5

New startup formation likely won’t be as robust as it was in the last cycle, as investors opt not to invest in businesses without a very clear path to durability and platform potential. And investors won’t be able to bank on multiple expansion as a key driver of returns – exit revenue multiples for all but the most exceptional companies will likely sit in the mid-to-high single digits.

The glory days of software are over: higher interest rates and commensurately lower valuations, less greenfield, and big questions around long-term competitive differentiation and profitability abound. But anyone who has ever argued that “the window to create wealth is closed” has been wrong. There are always opportunities for new startups to create and capture value. The investors who make money in the coming decade will be those who embrace these new, “Software 3.0” opportunities – rather than relying on the same opportunities that made them rich in the last cycle.

Vertical SaaS companies face fewer challenges than their horizontal peers. And exciting vertical opportunities abound – especially in the age of generative AI

The challenging headwinds in software – limited new market opportunities, crowded competitive landscapes and the feature arms race, and unclear paths to durably leverage AI – are most applicable to horizontal software businesses. There are more reasons to be optimistic about vertical software:

While there have been several vertical software successes (Toast, ServiceTitan, Veeva, Benchling, etc.), there’s more greenfield. Many vertical markets don’t yet have strong software incumbents

Vertical markets are usually smaller than horizontal ones, which limits the number of competitors – and the capital investments in those competitors

The domain expertise required to truly understand customer workflows and sales cycles creates natural barriers to entry

Vertical markets tend to be monopolistic, because only one business can credibly win the right to own all (or substantially all) of a customer’s workflows. Winners also become the system of record for their customers, making them very difficult to rip out. As a result, vertical software businesses don’t suffer from the expensive feature “race to the bottom” that horizontal ones do, creating more compelling dynamics around long-term defensibility and profitability

Excitement around vertical software isn’t new (if the number of market maps is any indication). But with many vertical markets in their early innings, many unicorns have yet to be minted. Opportunities certainly abound, especially in two specific areas: look for the next wave of vertical software companies to focus on solving inter-company collaboration and making heavy use of generative AI.

To date, vertical SaaS winners mostly owned their customers’ internal workflows. They found an important wedge to start serving customers and to become a mission-critical part of their operations (just as horizontal companies began by solving a narrow problem with an elegant point solution). Over time, they leveraged that wedge to expand into the entire customer organization: HR and payroll, supply chain, POS, CRM, customer service, scheduling and booking, intra-company communications, integrations, and finance. Owning payments was a key monetization strategy; rather than simply selling tools, companies scale revenue by taking a cut of all economic activity their customers generate.

Very little progress has been made, however, on solving inter-company collaboration. This is a big opportunity for vertical software companies to add value. In addition to building for core internal users, they’ll help their customers – via both collaboration tools and access to additional financial services – strengthen relationships with their ecosystem partners. Going “multiplayer” will enable vertical software products to not only create network effects that make them stickier and more durable, but also offer another monetization lever for them to extract customer value.

Of course, the most exciting opportunity for vertical software companies is the generative AI one. Industries with workflows that revolve heavily around information retrieval, synthesis, and creation (all guided by human judgement) are ripe for disruption from new vertical AI products: those tasks are exactly what LLMs are best suited to do. And because LLMs are a fundamentally transformative technology that meaningfully increases the scope of which problems software can solve, constraints in the old world don’t necessarily apply to the new one. For instance, it was long considered enormously difficult to sell software to professional services companies: law firms, management consulting outfits, and investment banks. Today, executives at all three are clamoring to buy AI products. Even if experimental budgets decline and enterprise use cases take longer to play out, the surface area for vertically-focused AI companies to attack has never been greater.

Why should investors be bullish about vertical AI startups if AI is primarily a sustaining innovation in application software? Whether they are new, AI-native startups or existing businesses incorporating intelligent features into their workflows, vertical AI companies don’t face the same problems around value capture that their peers attacking horizontal markets do. Those startups face well-capitalized incumbents who can afford expensive model training and inference costs, have strong customer relationships and own their customers’ workflows, and have access to the proprietary datasets required to properly adapt foundation models for their industry-specific use cases.

Fortunately, most vertical AI startups don’t face those incumbents. There’s ample room for them to form their own customer relationships, build new products, and create proprietary datasets. And because the execution work to build domain-specific apps is much more complex than the work required to build horizontal ones – which mostly look like thin chat interfaces and visualization tools on top of a foundation model API – early-moving vertical AI startups will be harder to copy. We’re already seeing exciting examples: Harvey and EvenUp attacking segments of the legal industry, Albert attacking chemicals R&D, and more. There may be dozens of defensible, durable vertical AI companies with strong pricing power and long growth runways built in the decade to come.

As opportunities to invest in new pure software businesses dry up, the most exciting businesses may be software-enabled services companies that aggressively leverage LLMs

“Services” has long been a dirty word in the venture world: services companies lack the predictable revenue streams of pure SaaS ones, generate lower margins, and don’t have the same sort of scalability and operating leverage in their business models due to ongoing, direct labor costs.

But as the opportunity set in pure software narrows, venture investors ought to reconsider their skepticism. Tech-enabled services businesses can certainly be a good fit for the venture model, which requires three things:

Companies must have a path to generating nine figures of high-gross-margin revenue within a decade of inception. This requires attacking large end markets. A fast-growing business that reaches $100M of revenue at 80% gross margins is likely a unicorn. Given the power law dynamics of venture fund returns, investing in companies without this expectation offers a poor risk/reward profile

A business’ strategy must require significant amount of invested capital to subsidize losses in the service of R&D investments (to build valuable and durable products) and growth (to acquire long-term customers). If a company doesn’t believe it needs capital, it makes no sense to sell a large share of the business to venture investors

There must be a compelling novelty to the business that poses technology risk, market risk, or execution risk. Without one or more of these risks, a business is likely to be too “consensus.” It’ll be too expensive or too easily copied – and its upside limited

Not every new tech-enabled services business should raise venture capital. The ones that should share several characteristics:

They attack massive – not just big – end markets, with tens of billions of dollars spent on traditional services. Because the services model generates lower gross margins than the software one, investors’ revenue expectations for venture-scale service businesses are even loftier than they are for software companies. Only services companies operating in enormous markets will meet these expectations

Software (the “tech-enabled” component of a service) meaningfully improves both customer experience and the business’ cost structure. Customers must care about technology and want to use it. And software must give service workers leverage to reduce costs and improve margins, relative to those of their traditional peers. The absence of CX and margin improvement makes the expensive investments in software development impossible to justify

The labor market that a business operates in has plenty of available workers. It’s very difficult to successfully operate a services business in a market with a labor shortage. Companies in those markets struggle to hire enough workers (which limits their speed and scale, and thus, their fit for the venture model); must re-skill workers in adjacent industries (which also limits speed and scale, and is often prohibitively expensive); or must pay exorbitant wages to attract talent (which ruins the economics)

They don’t require large physical infrastructure to operate. Services businesses which must make large property investments become capital-intensive very quickly. Early equity investors often face too much dilution, ruining their return profile

There are plenty of industries that fit these criteria, presenting opportunities for software-native operators to remake old-school, low-tech industries by offering a compelling software-enabled services solution: in pockets of insurance, healthcare, finance, and more.

The real opportunity in tech-enabled services, however, is AI-enabled services companies, which represent a logical extension of the vertical AI wave. Industries dominated by “bits” work that can be replaced by LLMs – think bookkeepers, insurance adjusters, and healthcare billing specialists, not freight carriers – can be disrupted by entrepreneurs building services companies with an AI-first mindset. And while AI presents structural margin challenges for pure software companies, it’ll lead to margin expansion for services ones:

In the short-term, services companies will build AI-powered software to turbocharge the productivity of their service workers, improving their margin profiles as they get even more leverage on their workers than they would using “unintelligent” software

In the long-term, services companies will use LLMs to replace large parts of their labor forces entirely. Substituting wages for inference costs will enhance margins even further. And LLMs will enable them to sell high-velocity, high-quality finished work – rather than just providing software-augmented labor.

Importantly, substituting labor for LLMs does more than just improve margins. It expands the universe of successful service businesses that entrepreneurs can build:

Industries with labor shortages have typically been a bad fit for the labor-intensive, tech-enabled services business model. AI-enabled services businesses largely solve the labor shortage problem: entrepreneurs who can’t find enough workers can simply turn to machines

LLMs will usher in the transformation of certain labor marketplaces into direct service providers – or the creation of new service businesses to replace them. The marketplace business model has historically been a highly profitable, high-ROIC one: solve a complex coordination problem and earn a high-margin “tax” on all economic activity arranged via the marketplace with very little invested capital required to deliver supply. But if AI dramatically drives down the cost of providing marketplace supply (labor), why settle for only a small share of the economic activity rather than earning all the revenue yourself? The advent of powerful LLMs will either (1) push existing labor marketplaces to become AI-enabled services companies or (2) if incumbent marketplaces are uncomfortable with the innovators’ dilemma of hurting their core match-making business and pivoting to a first-party services model, enable the creation of entirely new services startups to disrupt them

AI-enabled services companies lack the elegant business model of pure software ones and may never generate the same margins, so investors must be very disciplined about which services businesses they invest in, and at what valuations. But those who embrace the opportunity – rather than turn their nose up at it – will ride this next wave.

The best investors will accept the new environment facing software companies, explore new areas, and re-write their old playbooks

Investors can’t rely on the tailwinds that propelled the last wave of software winners or another frothed-up bull run to make money. Those who do will generate uninspiring returns – if they generate any returns at all. How will the best investors make money moving forward?

Just as important as what changes is what doesn’t: great investors will continue to invest with a founder-first mindset. The venture industry is ultimately driven by outliers. Only a small number of companies really matter, and there are always “N of 1” founders who don’t care about the macroenvironment and who have a vision for the future that nobody else sees. The best capital allocators of the past haven’t necessarily been those with the most compelling ideas themselves; they’ve been the ones humble enough to recognize greatness in founders (whatever that means to them) and sharp, trusted, and helpful enough to win allocations in their deals. That identifying excellent talent – not developing the best market or business insights – has historically led to the best returns may be intellectually unsatisfying for investors who want to generate alpha from their own ideas. But it has been true in the past and will be true in the future.

Outside of maintaining a founder-first mindset, the best investors will avoid calling the same plays they did in the last cycle and re-write new ones instead.

Invest in best-in-class, narrow point solutions → Invest in “compound startups” or companies with a very clear path, from the outset, to becoming a multi-product, platform business

Starting small, remaining focused, and building an amazing product to solve a very narrow problem has been a great way to start a company. The biggest venture-scale successes of the future, however, will probably take a different approach. Some will follow today’s hot VC trend and build compound startups: companies that become multi-product very quickly. These are hot for good reason; Rippling, the most prominent compound startup, may be the highest-quality private software company today. The compound model can certainly work, but these startups must have a clear reason why they’re not just blowing enormous sums of capital on R&D and S&M to become undifferentiated players who are broader than everyone but better than no one.

Other winners may look more like traditional startups: narrow products with the most elegant solution to a specific problem. But these companies, unlike some of the startups that became big over the last decade, will have a coherent narrative – not a hand-wavy one – from the outset around how they become multi-product, platform-esque systems of record with the right to win many of their customers’ workflows.

Invest in businesses riding the prevalent technological wave → Think critically about whether new technological waves will benefit newly formed businesses, and invest only in specific areas where new companies can both create and capture value

The shift to software delivered via the cloud and the concurrent push to digitize enterprise workflows presented massive opportunities for new entrants to create and capture value over the last decade. Today’s biggest technological wave – the advent of LLMs – likely won’t benefit most horizontal application startups in the same way. It won’t be enough to create massive consumer surplus; investors must be much more thoughtful about specific places where startups can actually capture the value created by new technologies. In this age of generative AI, they should be laser-focused on vertical software.

Get exposure to great companies, even at extreme valuations, and bet on a sustained period of elevated exit multiples → Accept that market headwinds and a normal forward-looking interest rate environment require a delicate balance between gaining exposure to good companies and discipline around entry prices

Many private tech investors haven’t historically been sophisticated financiers or savvy business analysts. The ones who make money in the coming decade will be creative around structured products, willing to invest across the capital structure, sensitive to the macroenvironment, and certainly rigorous around valuation. They’ll recognize that a great product doesn’t necessarily make a great business, and a great business doesn’t necessarily make a great investment. Even considering the long-term nature of private technology investing, price matters.

Given the power law of venture, getting exposure to the companies that matter is critical. But exposure itself isn’t enough: unless by sheer luck you exit in a generationally frothy environment, you need to own a meaningful stake in those companies to generate excellent returns – and hitting your ownership targets in enough companies requires price discipline. Investors shouldn’t be in the business of getting lucky or collecting infinity stones to showcase on their website – they should be in the business of making money. The best will assume grounded exit valuations for their companies and invest accordingly.

Avoid services companies, because they lack the high-margin, scalable elegance of pure software ones → Embrace high-quality service businesses with venture-scale characteristics, especially ones that leverage LLMs to improve their cost structures

There simply aren’t as many exciting opportunities for new software companies as there once were, and the startups that do breakthrough – like vertical AI ones – may face structural margin challenges relative to today’s software companies. The venture investors who succeed in the coming decade will embrace this reality, be open-minded, and accept that valuable “tech” companies may look different than they used to. AI-enabled services companies attacking massive markets with software that customers actually care about could become some of Silicon Valley’s most valuable businesses in the next cycle.

Thanks to everyone who provided feedback on this piece! If you have questions, comments, or feedback, please reach out: andrewziperski [at] gmail [dot] com.

Data as of 9/19/2023

Drawdown based on data between 11/19/21 and 10/14/22

Data as of 9/1/2023

10Y UST yield; data as of 9/19/2023

Data as of 9/15/2023