The Stock-Based Compensation Sleight of Hand

We’re thinking about stock-based compensation accounting – and cash profitability – the wrong way.

Stock-based compensation discourse always picks up when software falls out of favor with investors. We saw this frequently during the SaaS crash of 2022 and are seeing it again now as software names sell off due to the “AI kills software” narrative.

Loud SBC discourse on X is usually a sign that stocks are at/near their bottom, but the SBC discussion deserves an honest refresh nonetheless: the debate everyone has revolves around whether SBC is “real,” but the one we should be having is whether SBC ought to be added back to operating or financing cash flow.

The former debate is rather uninteresting given its one-sidedness. SBC is obviously a very real cost of hiring and retaining employees, who treat equity grants as a critical component of their TC. Characterizing SBC as “fake” – and adjusting it out of opex – completely distorts the financial profile of a business and its true profitability. GAAP methods for how to value and when to recognize SBC may be imperfect, but Adjusted EBITDA figures that entirely exclude SBC are a farce.

Herein lies the more interesting discussion around SBC: not whether it’s real, but how it should be treated as an accounting matter. Today, GAAP requires companies to recognize SBC as a non-cash operating expense on the income statement and as a corresponding “add-back” to operating cash flow. This approach is totally logical, but I believe it ignores a critical distinction: while how much to compensate employees is an operating decision, how to pay for that compensation is a financing one.

Paying employees in stock is no different in substance than selling stock to investors and using the proceeds to pay employees in cash. That is decidedly a financing activity. GAAP rules aside, every investor and management team should treat SBC in a way that reflects its economic substance: an operating expense, but a financing cash flow. Concretely, we ought to adjust GAAP cash flows by adding SBC expense back to cash flow from financing, rather than to operating cash flow.

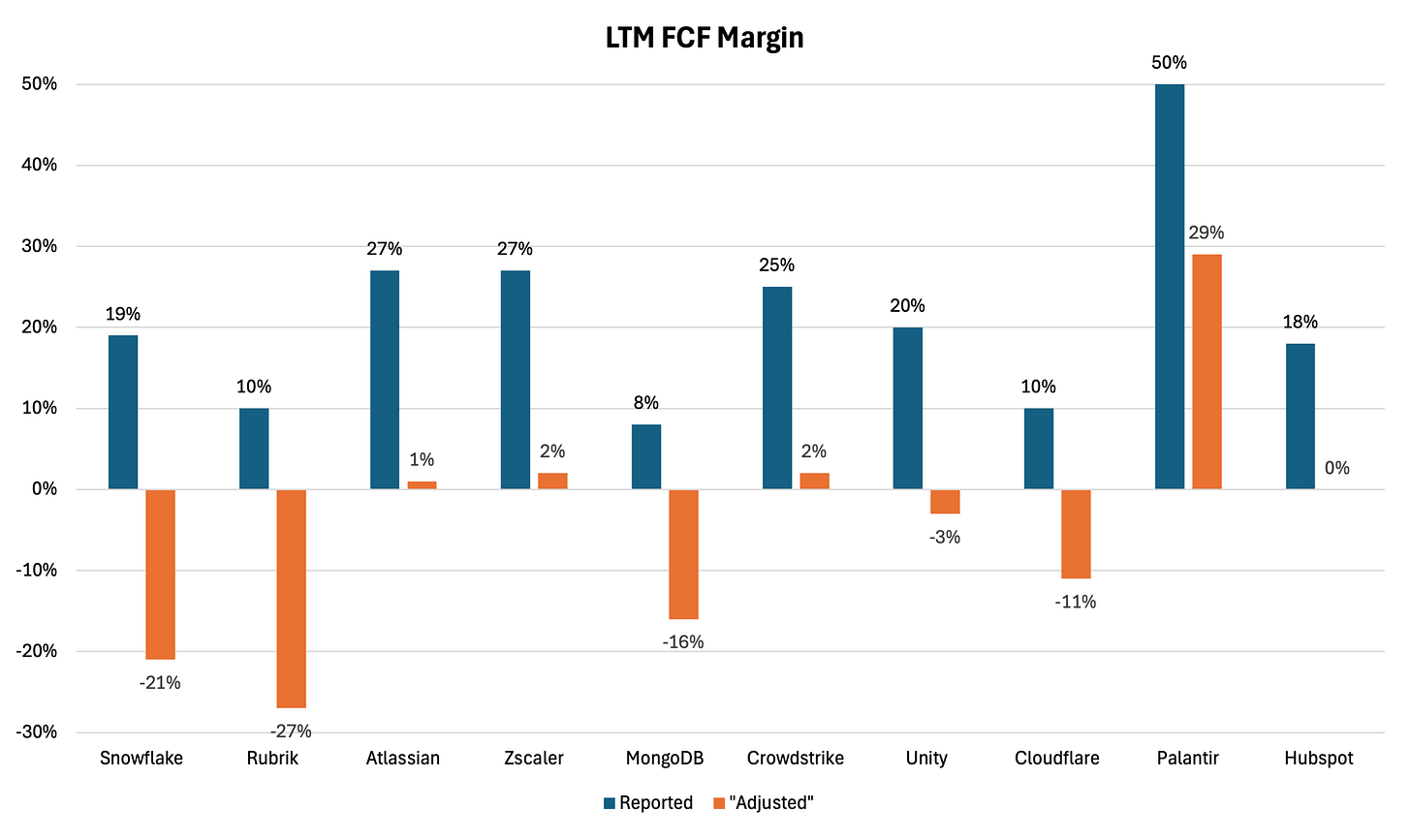

Why does this matter? When you treat SBC this way, you unlock two important insights. First, because every management team should strive to maximize long-term FCF per share, burdening FCF with SBC expense makes it very clear that SBC is a real cost to shareholders – and reveals which companies can actually generate economic profits. It's striking to see the difference between reported and my “adjusted” FCF margins for high-flying software companies. Many “cash-generative” companies don’t really generate economic profits for shareholders.1

The way that we talk about things impacts the way we perceive them. Today, GAAP rules that allow management teams to pull an accounting “sleight of hand” meaningfully change not only the way that investors evaluate companies, but also the way that those companies operate and finance themselves.

To that end, treating SBC this way makes it easier to reason about it as a deliberate capital allocation choice rather than a throwaway “thing that companies just do.” The way that a company finances its employee compensation plan ought to be a deliberate decision in pursuit of maximizing FCF per-share. When a company’s stock is expensive, management should shift the compensation mix to favor stock – in the same way that it would be willing to sell stock at a high price to fund other initiatives. Conversely, when its stock is cheap, management should favor cash compensation, for the same reason that it wouldn’t sell tons of stock at firesale prices.

Re-framing SBC as a deliberate capital allocation choice reveals how silly it is when management teams characterize share repurchases as a “strategy” to offset SBC-based dilution. Stock buybacks and SBC don’t thoughtlessly go hand-in-hand; if anything, tying them together is backwards! Making heavy use of SBC is a good capital allocation decision when a stock is “expensive,” but buybacks are accretive only when a stock is “cheap” in light of the return on capital for other initiatives.

SBC is a wonderful tool to align long-term incentives between management, employees, and shareholders – it’s part of what made Silicon Valley so great. But it’s certainly time to put the “is it real” debate to rest. And more importantly, it’s time to adjust not only the way we account for it, but also how, when, and in what amounts we use it.

Data as of 8/22/2025